Treaty of Point Elliott: Indigenous & Settlement History

The Treaty of Point Elliott, signed in 1855 at present-day Mukilteo, Washington, drastically reshaped Coast Salish homelands by extracting vast land cessions while formally reserving key rights that still govern Indigenous–settler relations across Puget Sound.

Understanding this treaty reveals how dispossession and survival unfolded together, as tribal nations defended sovereignty, cultural continuity, and resource rights under intense colonial pressure.

Coast Salish homelands before 1855

Before American officials arrived to negotiate, Coast Salish nations such as the Duwamish, Suquamish, Snohomish, Snoqualmie, Skagit, Lummi, and others lived in dense village networks tied to watersheds, shorelines, and mountain corridors in what are now King, Snohomish, Skagit, and Island Counties. Seasonal rounds of fishing, shellfish harvesting, hunting, and gathering linked communities around the Salish Sea, supported by kinship, trade, and shared responsibilities for lands and waters.

Rivers like the Duwamish, Snohomish, and Skagit, along with Puget Sound inlets, served as transportation corridors, food sources, and spiritual anchors. Stories, ceremonies, and languages were intimately bound to particular places, forming a cultural landscape that settlers often misread as “unused” land rather than carefully governed territory.

Why the United States pushed for treaties

By the early 1850s, U.S. leaders wanted to accelerate non-Native settlement, logging, and agriculture in Puget Sound, and federal policy called for treaties to clear Indigenous title before issuing homesteads. Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens was directed to secure a series of treaties across Washington Territory, arriving with pre-drafted documents to speed negotiations and standardize terms.

For U.S. officials, the Treaty of Point Elliott promised millions of acres for settlement while concentrating Native people on a smaller number of reservations that could be monitored and reshaped into farming communities. For Indigenous leaders, treaty councils were emergency negotiations to protect their peoples’ survival by holding onto fishing, hunting, and gathering practices in the face of escalating settler pressure.

The treaty council at Point Elliott

On January 22, 1855, tribal leaders gathered at bək̓ʷəɬtiwʔ (Point Elliott), now Mukilteo, for a council with U.S. officials conducted largely in English and Chinook Jargon, a trade language that was not a first language for most attendees. This created serious potential for misunderstandings about legal concepts, land boundaries, and the long-term meaning of treaty provisions.

Signatories included Duwamish and Suquamish leader siʔáb Si’ahl (Chief Seattle), along with leaders representing Snohomish, Snoqualmie, Lummi, Skagit, Swinomish, and other Coast Salish groups. The Duwamish were listed first in the treaty text, and Chief Seattle’s name appears at the top of the Native signatures, reflecting federal recognition of his political importance at the time.

Land cessions and new reservations

Under the Treaty of Point Elliott, signatory nations ceded a sweeping area of central and northern Puget Sound, extending toward the Cascades and encompassing the future sites of Seattle, Everett, and many surrounding communities. Within this expanse, more than 54,000 acres associated with Duwamish homelands—including lands that would become Seattle, Renton, Tukwila, Bellevue, and Mercer Island—were transferred in exchange for promised protections and payments.

The treaty created several reservations, including Tulalip, Lummi, Swinomish, and Port Madison (Suquamish), intended as shared homelands for multiple bands brought together under new political frameworks. Yet some signatory groups, including the Duwamish and Snoqualmie, never received separate reservations, forcing many families to relocate to other reservations, settle on marginal lands, or disperse into nearby towns to survive.

Reserved fishing and resource rights

Even as they ceded land, Indigenous negotiators insisted on reserving traditional resource practices, which became central to Article 5 of the treaty. The treaty explicitly protected the right of signatory tribes to fish at their “usual and accustomed” grounds and stations and to hunt and gather roots and berries on open and unclaimed lands, recognizing that these activities were essential for sustenance and cultural life.

In the twentieth century, these clauses shaped major legal battles over salmon fisheries in Washington. The 1974 Boldt decision affirmed that treaty tribes were entitled to up to half of the harvestable fish and co-management authority over fisheries, confirming that reserved rights in the Treaty of Point Elliott are binding obligations on the United States, not historical footnotes.

Immediate consequences for Indigenous communities

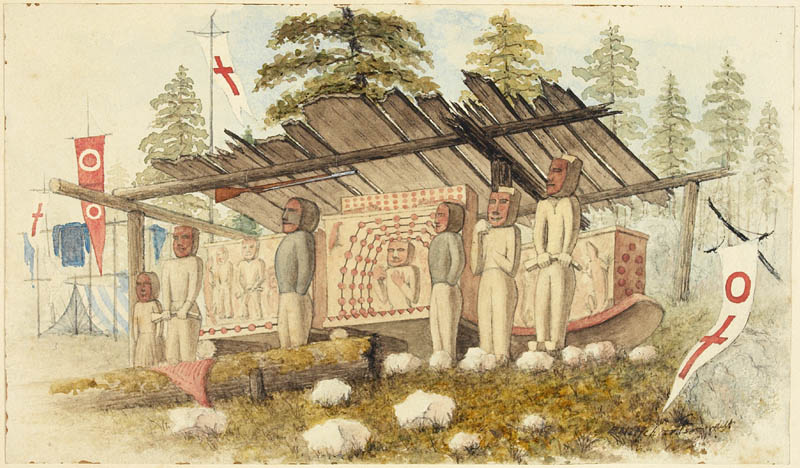

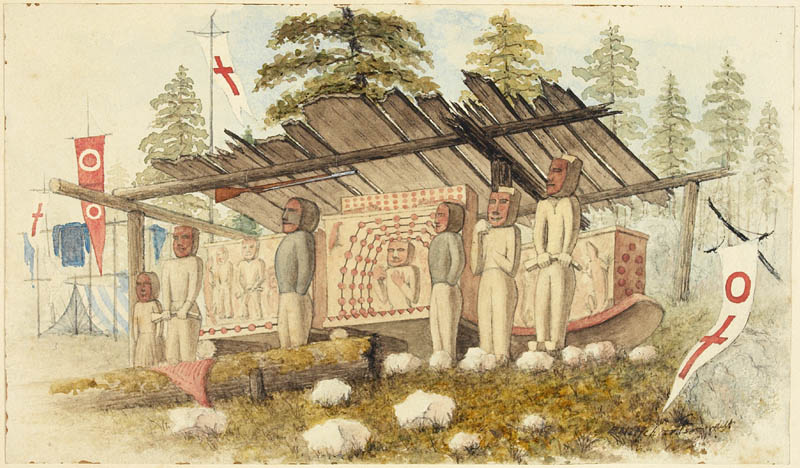

In the years following 1855, the treaty’s impacts were felt in disrupted village patterns, forced relocations, and rising settler encroachment, often beginning even before formal ratification in 1859. Disease outbreaks, missionary campaigns, and federal agents’ efforts to suppress cultural practices compounded the upheaval, targeting long-standing governance systems and spiritual traditions.

Some treaty promises went unfulfilled, such as a dedicated reservation for the Duwamish, leaving signatory communities without the land bases they expected. Yet Coast Salish people continued to fish, travel, and gather across their territories, sustaining kinship networks and ceremonies that affirmed ties to ancestral places despite official attempts at confinement.

Ongoing legacies and recognition struggles

Today, tribal governments such as the Tulalip Tribes and the Suquamish Tribe identify as successors to bands that signed the Treaty of Point Elliott and continue to exercise inherent sovereignty and treaty-reserved rights. These nations lead fisheries co-management, habitat restoration, and cultural revitalization efforts that link contemporary governance directly to treaty commitments.

Unresolved issues remain, including the Duwamish Tribe’s long-running effort to secure federal recognition and full implementation of promises made in 1855. Activism around salmon recovery, climate impacts, and land use also increasingly invokes the treaty as a living document that defines shared responsibilities for the region’s lands and waters.

Intertwined Indigenous and settler histories

The Treaty of Point Elliott binds together Indigenous and settler histories: the growth of cities like Seattle, Everett, and Mukilteo depends on lands ceded under the treaty, while the endurance of tribal nations rests on the enforcement of rights that were never surrendered. For many Coast Salish communities, the treaty is not simply a record of loss but a legal and moral framework that affirms sovereignty, stewardship, and relationship to place.

Recognizing this intertwined history invites residents of the region to engage with tribal nations as ongoing partners in caring for salmon, shorelines, and ancestral territories, rather than treating the treaty as a closed chapter. In this sense, the Treaty of Point Elliott continues to shape how people in the Puget Sound area understand justice, land, and belonging—and it also frames how today’s communities in places like Mukilteo think about caring for homes, and neighborhoods.